Huntington disease

Huntington disease is a progressive neurodegenerative condition that causes motor, cognitive and psychiatric decline. It is inherited, and affected individuals have a 50% chance of passing it on to their children.

Overview

Huntington disease is a progressive neurodegenerative condition characterised by motor, cognitive and psychiatric decline. It is inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern, which means that first-degree relatives (parents, children, siblings) of an affected individual have a 50% chance of being affected themselves.

Clinical features

The prevalence of Huntington disease in the UK is around 1 in 10,000, with the peak onset of motor symptoms occurring between the ages of 40 and 45.

Cognitive and psychiatric problems are often present at diagnosis, although affected individuals most commonly present with a movement condition. Involuntary movements (chorea) may be prominent, with bradykinesia, dystonia, mental disturbances and cognitive decline becoming more notable as the condition advances.

Clinical signs of Huntington disease

- Early: chorea, clumsiness, agitation, irritability, anxiety, delusions, disinhibition, apathy, hallucinations, depression.

- Middle: dystonia, chorea, weight loss, speech and swallowing difficulties, ataxia, slow voluntary movements, progressive cognitive decline.

- Late: dementia, rigidity, bradykinesia, inability to walk, inability to speak, swallowing problems, inability to care for oneself.

The median survival time after onset is 15 to 18 years, with the average age of death around 55 years.

Genetics

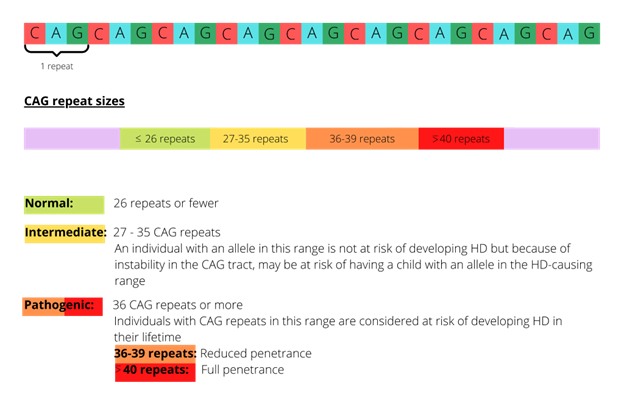

Huntington disease is caused by a heterozygous expanded CAG trinucleotide repeat expansion in the HTT gene.

In the HTT gene, there is a DNA segment known as the CAG repeat, in which the three nucleotides C, A and G appear multiple times in a row. The number of repeats varies between individuals, and an expanded number of repeats results in Huntington disease (see figure 1). There is a broad association between the number of CAG repeats and the onset of clinical manifestations of Huntington disease.

Figure 1: CAG expansions in the HTT gene and risk of development of Huntington disease symptoms

Inheritance and genomic counselling

Huntington disease is inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern. Affected individuals have a 50% chance of passing the condition on to their children. The CAG repeat size does not correlate well with age of onset, clinical phenotype or progression, all of which may vary considerably, even between individuals in the same family. Individuals with expansions of 55 CAG repeats or more are at risk of early onset symptoms (juvenile- or paediatric-onset Huntington disease), although it is very rare in those under 10 years old.

Asymptomatic individuals at risk of developing Huntington disease can be offered predictive or pre-symptomatic testing. Due to the implications of the diagnosis for an individual’s relationships and financial and psychological status, pre-symptomatic testing is offered through clinical genetics services only. A series of appointments is recommended, including a mental health assessment, to support the individual in their decision.

Management

The mainstay of management for Huntington disease is supportive treatment and symptom control. It is common for patients to have had treatment for mental health conditions such as anxiety and depression before a formal diagnosis.

Multidisciplinary management is vital, with input from neurologists, neuropsychiatrists, geneticists, physiotherapists, speech and language therapists and occupational therapists.

A wide range of potential therapies are under investigation in both human and animal models.

Resources

For clinicians

- GeneReviews: Huntington’s disease

- NHS England: National Genomic Test Directory

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke: Huntington’s disease

- US National Library of Medicine: ClinicalTrials.gov database

References:

- Baig S, Strong M, Rosser E and others. ’22 years of predictive testing for Huntington’s disease: The experience of the UK Huntington’s Prediction Consortium’. European Journal of Human Genetics 2016: volume 24, pages 1,396–1,402. DOI: 10.1038/ejhg.2016.36

- Craufurd D, MacLeod R, Frontali M and others. ‘Diagnostic genetic testing for Huntington’s disease‘. Practical Neurology 2015: volume 15, issue 1, pages 80–84. DOI: 10.1136/practneurol-2013-000790

- MacLeod R, Tibben A, Frontali M and others. ‘Recommendations for the predictive genetic test in Huntington’s disease‘. Clinical Genetics 2013: volume 83, issue 3, pages 221–231. DOI: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2012.01900.x

- Stoker B, Mason SL, Greenland JC and others. ‘Huntington’s disease: diagnosis and management‘. Practical Neurology 2022: volume 22, issue 1, pages 32–41. DOI 10.1136/practneurol-2021-003074

For patients

- NHS England: Huntington’s disease

- Huntington’s Disease Association