Prader-Willi syndrome

Prader-Willi syndrome is a rare genetic condition characterised by neonatal hypotonia and poor feeding, childhood hyperphagia, obesity and intellectual disability.

Clinical features

Neonate and infant

- Severe hypotonia (can also be present in the fetus and may present as reduced fetal movements).

- Poor sucking ability, lethargy and failure to thrive. Feeding difficulties generally improve by six months of age.

Childhood

- Developmental delay and intellectual disability.

- Behavioural difficulties (obsessive-compulsive disorder, temper tantrums, stubbornness).

- Hyperphagia and obesity, with food behavioural anomalies that include persistence in asking for extra food, food seeking, hoarding and stealing (either food or money to buy food) and the eating of inappropriate substances (not food).

- Weight increase can occur from two years to four and a half years, before the onset of hyperphagia.

- Hyperphagia increases between four and a half years and eight years and, if access to food is not controlled, there will be weight gain and morbid obesity.

- Hypothalamic hypogonadism (genital hypoplasia, incomplete pubertal development and usually infertility).

- Short stature.

- Small hands and feet.

Facial features

Characteristic facial features include:

- almond-shaped eyes;

- thin upper lip and narrow nasal bridge;

- high prominent forehead; and

- narrow bifrontal diameter.

Other medical associations

- Deletion of chromosome 15q11 can be associated with oculocutaneous albinism.

- Growth hormone deficiency.

- Ventriculomegaly on MRI brain scan.

- Seizures.

Genetics

Prader-Willi syndrome (PWS) is an imprinted condition caused by disruption of a number of paternally inherited genes, most notably SNRPN, in the Prader-Willi critical region (PWCR) at chromosome location 15q11.2-15q13 (see figure 1).

Figure 1: Genetic mechanisms of Prader-Willi syndrome

- Most children with PWS have a deletion of the PWCR.

- 20%–30% of cases are caused by maternal uniparental disomy (UPD), in which both alleles are maternally derived with no paternal contribution.

- Imprinting anomalies are responsible for a small number of cases.

- Several genes in the PWCR are methylated depending on their parental origin.

- In PWS, the genes in the PWCR have the maternal methylation pattern and are therefore switched off where they would be normally switched on.

- In rare cases, this methylation anomaly is due to a (potentially heritable) deletion in a downstream imprinting centre (figure 1 and table 1).

It is important to bear in mind the following genetic considerations.

- Microarray will detect the majority of PWS cases, as deletions are the most common cause. However, if PWS is in your differential, testing should be undertaken through the indications R48 Prader-Willi syndrome or R69 Hypotonic infant, because these will detect other forms of PWS.

- Microarray will not be able to differentiate between PWS and Angelman syndrome because it is not possible to determine whether the deletion is on the maternal or paternal allele. Further testing is required to determine this.

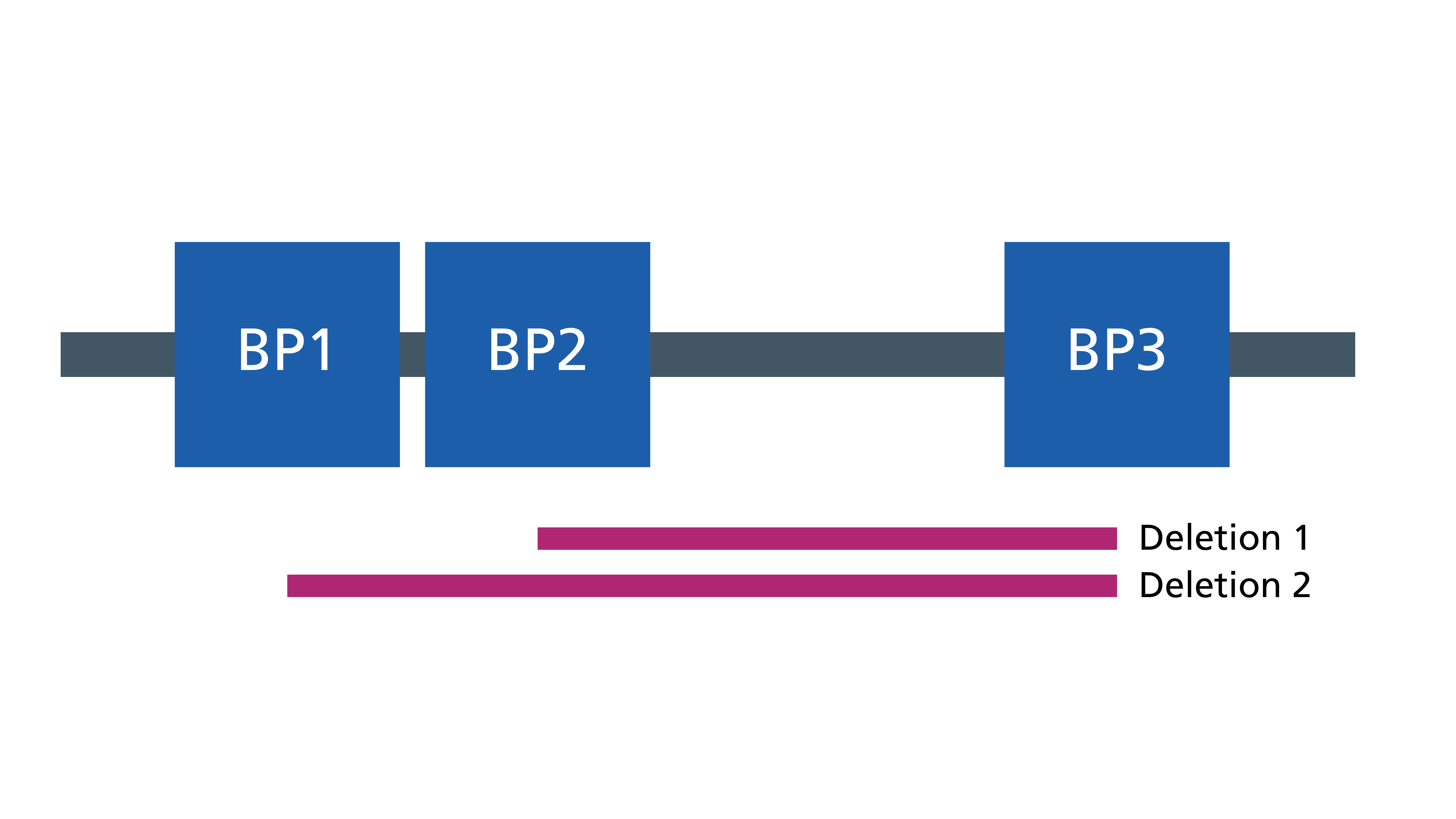

- Most deletions are one of two sizes. This is because the deletion is generated by misalignment of very similar genetic blocks (called low copy repeats) on either side of the deleted region. These blocks are called BP1, BP2 and BP3 (see figure 2). One of the two sizes of deletions extends from BP1 to BP3, the other extends from BP2 to BP3.

Figure 2: The two sizes of deletions

For information about testing, see Presentation: Clinical suspicion of Prader-Willi syndrome.

Inheritance and genomic counselling

Where both parents are unaffected by PWS, the risk to the siblings of an affected child (the sibling recurrence risk) depends on the genetic mechanism.

Table 1: Genetic mechanism of PWS and counselling implications

| Genetic mechanism | Proportion of children with PWS | Sibling recurrence risk (assuming both parents unaffected) |

| Paternal 15q11.2 deletion | 65%–75% | Less than 1% |

| Maternal uniparental disomy | 20%–30% | Less than 1% |

| Imprinting anomaly: no deletion of imprinting centre | 2% | Less than 1% |

| Imprinting anomaly: deletion of imprinting centre | Less than 0.5% | 50% if father has the same imprinting centre deletion |

| Chromosome translocation disrupting 15q11.2-15q13 | Less than 1% | Depends on chromosome translocation |

Management

Management of children with PWS is complex and aims to reduce weight gain, encourage physical activity and optimise learning. Weight gain is not inevitable and can be avoided if access to food is controlled. Children are typically managed under a community paediatric team (including occupational therapy, physiotherapy and speech therapy) and input from paediatric gastroenterology, endocrinology, dieticians, orthopaedics and child and adolescent mental health services may be helpful. You can find recommended management guidelines in the list of resources below.

All infants with PWS should be referred to a paediatric endocrinologist for consideration of growth hormone treatment. This should be done early on (current guidelines recommend that growth hormone therapy begins before the individual is one year old). Growth hormone therapy has been shown to be beneficial for children with PWS in treating their short stature; it also helps reduce fat mass and improve mobility.

Resources

For clinicians

- Genomics England: NHS Genomic Medicine Service (GMS) Signed Off Panels Resource

- National Organization for Rare Diseases: Prader-Willi syndrome

- NHS England: National Genomic Test Directory

- OMIM: 176270 Prader-Willi syndrome

- Patient Info: Prader-Willi syndrome

- Prader-Willi Syndrome Association UK: Professionals you should see

- U.S. National Library of Medicine: ClinicalTrials.gov database

References:

- Finkel RS, Mercuri E, Meyer OH and others. ‘Diagnosis and management of spinal muscular atrophy: Part 1: Recommendations for diagnosis, rehabilitation, orthopedic and nutritional care‘. Neuromuscular Disorders 2018: volume 28, issue 2, pages 103–115. DOI: 10.1016/j.nmd.2017.11.005

For patients

- NHS Health A to Z: Prader-Willi syndrome

- Prader-Willi Syndrome Association UK